[in commemoration of Women's History Month]

“Is There a History of Women?”

In spring 1974, in my first year of graduate school in history at UT Austin, one of the truly distinguished American historians of the era, Carl N. Degler (Pulitzer Prize winner and author of books still relevant today such as *Neither Black Nor White* and *Out of our Past*) spoke at a graduate-student luncheon on campus on this topic. A few weeks earlier, he had given the same address at Oxford, upon the occasion of its first admission of women students.

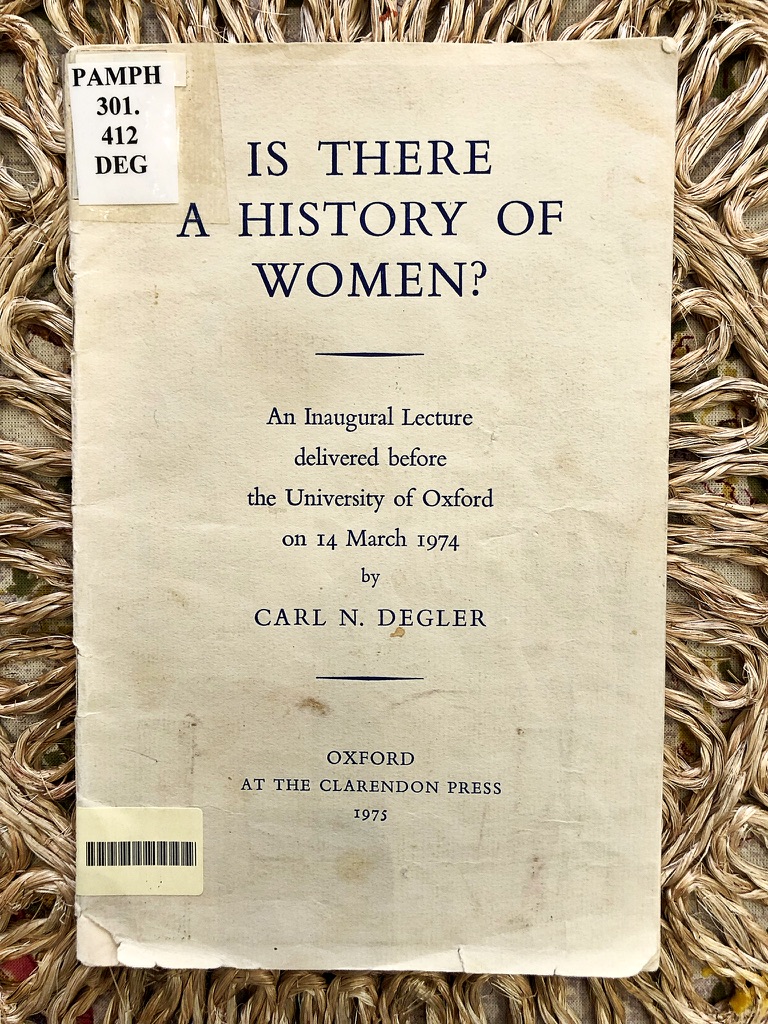

Yesterday I received a used copy of that speech (a deaccessioned library copy).

Degler began (remember, this is ’74): “[W]omen have been defined out of history” and “it is evident that women are excluded because it was assumed that in writing about men one was automatically writing about women, that, in fact, the concerns and interests of women were identical with those of men.” But he quickly repudiated “the assumption that women have no history separate from that of men” and provided a more accurate title for his speech: “Why do I think there is a history of women, and what is its nature?”

His reasoning: “women are not men socially any more than they are physiologically. And when we consciously recognize that fact . . ., we begin to recognize that our conception of the past alters. For if women are indeed different, . . . then they must affect history differently from the way men do, and, conversely, history must affect them differently from the way it affects men.”

One of the ways, the speaker observed, that women considered as a sex—and not as a social group or class—have shaped history, and that history has affected them, is in the matter of health. He reviewed one instance there, the special interest of women in birth control and the widespread experience of American women during the 19th century with abortion.

His conclusion: “Women are different from men. . . . Their past cannot be subsumed under the history of men. . . . it is that difference that justifies, indeed, requires a history of women.”

Degler was percipient. He was hardly the first to focus on the case for women’s history. He cited and paraphrased Simone de Beauvoir (*The Second Sex*) and the great Mary R. Beard (her book, *Woman as a Force in History*), But Degler's address in 1974 was, I believe, timely and helpful to show male historians of the day that there is a genuine need for women’s history and to foster an appreciation of those women historians already then tilling that field.

Four years later, the first "Women's History Day” was observed in Sonoma County, California, at the urging of historian Gerda Lerner and the National Women's History Alliance. In 1980, the celebration became a national week and in 1987 expanded to a month. Historiographically, much has been accomplished in the following decades although much more remains to be researched and written; and it is important for men who care about history to be both aware and engaged.

I am celebrating five women in my maternal ancestry, direct and collateral, who have compelling individual histories: (i) my great grandmother Mattie L. Morrison, who, after a financial disaster rendered my great grandfather Julian completely helpless, stepped up to found and run a private sanitarium, really the first hospital in Pecos, Texas, by which she supported, raised, and sent for higher education her six children; (ii) my grandmother Alice Morrison Glover, who took a degree from what is now Texas Women’s University and taught school, married my grandfather Preston Glover, bore my mother, and then suffered a mental illness for which she was, tragically, institutionalized for the rest of her life; (iii) my mother Peggy Glover Daniel, who majored in geology, married my father and bore me and my brother James, taught earth science in junior high school for 25 years, and finally, in her late fifties and early sixties, got and held the geological job of her dreams with Exxon Production Research, (iv) my great aunt Eula Morrison, who as a single woman owned and operated a Dairy Queen in a rough and tumble town, Odessa, Texas, in the 1940s and 1950s; and (v) my second cousin on the Morrison side, who died this past December, the redoubtable Sarah Weddington, whose first case right out of UT Austin’s law school was Roe v. Wade.

To bring this essay around to the present, I will acknowledge my concern that a male-centric if not misogynistic reaction to women’s history may be commencing. Today I read in the online journal *The Tyler Loop* (published in Tyler, Texas, 100 miles east of Dallas) that the Superintendent of Schools there has pulled 200 books from the shelves of the public schools for “review" and then to a decision to keep or to ditch. Among the two hundred titles are five books about the history of abortion and Roe and at least three dozen about teen pregnancy and sex education (e.g., *Everything You Need to Know About Growing Up Female* and *It’s A Girl Thing: How to Stay Healthy, Safe, and In Charge*)—and to cap it off, one book considered for banning is titled *The Year They Burned the Books*! Are we entering some sort of new Dark Ages? This vignette of current-day book-banning from a nearby city of about 100 thousand residents illustrates that we need women’s history more than ever.