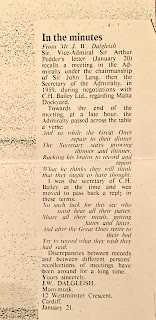

In 1970 my parents met and became friends with a British couple, Jane and J.W. "Jamie" Dalgleish of Cardiff, Wales. My mother is now 92 and in going through her "archives" just found this photocopy of a newspaper clipping. It is a letter to the editor of the London Times, undated[1], written by Jamie.

I see it in a point for legal historians.

Jamie Dalgleish was an officer of C.H. Bailey Ltd., a venerable firm engaged in the business of drydocks and related engineering services. In this letter to the editor, he replies to an earlier letter to editor of the London Times by an English vice-admiral, Sir John Lang, recalling a negotiating meeting held in the Admiralty in 1959 (so more one or two decades earlier) with Jamie's company regarding "Malta Drydock."

In that prior letter, Lang had recalled the navy's representatives passing a note across the table to the C.H. Bailey Ltd. team, which included Jamie. It was in verse:

And so while the Great Ones

repair to their dinner

The Secretary stays growing

thinner and thinner.

Racking his brains to record and report

What he thinks they will think that they ought to have thought.[2]

Jamie was that Secretary, and he reports in his letter to the editor that he passed back a reply:

No such luck for this sec[retary] who

must hear all their patter.

Share all their meals,

getting fatter and fatter.

And after the Great Ones retire to their bed

Try to record what they wish they had said.[3]

Jamie concluded his letter with these words: "Discrepancies between records and between different persons' recollections of meetings have been around for a long time."[4]

I salute those Brits' quick wits. And to Jamie's conclusion I would add only a triple exclamation point!!! Oral history interviews are important and so are legal and other documents deposited into archives. When they match up, the historian can rest a little more easily than when they don't.

_______________

[1] Based on my parents having received this, and because in this letter Jamie mentions that he "was secretary of C.H. Bailey at the time," I deduce that it must have been published well after 1970, during his retirement and before Jamie's death, which was in the eighties. (Note to self: always write the date on any clipping or copy thereof!) I cannot find it online.

[2] Emphasis added by me.

[3] Emphasis added by me.

[4] Emphasis added by me.